The Monaco Grand Prix often produces a controversy and this year was no exception, as Lewis Hamilton lost a certain victory due to a decision to pit with 12 laps to go.

It was the most costly pit lane decision since Ferrari pitted Fernando Alonso at the wrong moment in Abu Dhabi, losing the 2010 world championship as a result. It reminds us that in a sport where hundreds of important decisions get taken every race, it only takes one mistake like this for the spotlight to go onto the engineering group who decide the race strategy. Helping fans to understand this world and why the decisions are taken is the objective of the UBS Race Strategy report. So, as usual, we will provide a detailed, objective analysis of what went wrong and look at some other interesting strategy calls in the race.

It was the most costly pit lane decision since Ferrari pitted Fernando Alonso at the wrong moment in Abu Dhabi, losing the 2010 world championship as a result. It reminds us that in a sport where hundreds of important decisions get taken every race, it only takes one mistake like this for the spotlight to go onto the engineering group who decide the race strategy. Helping fans to understand this world and why the decisions are taken is the objective of the UBS Race Strategy report. So, as usual, we will provide a detailed, objective analysis of what went wrong and look at some other interesting strategy calls in the race.

When decisions go wrong

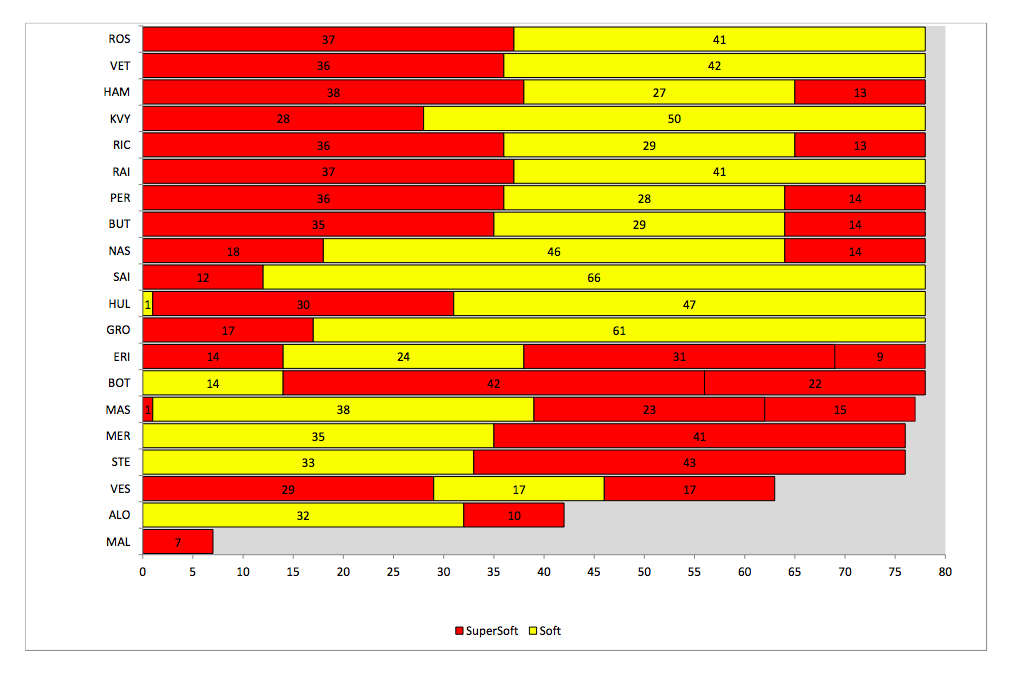

With a new and more robust supersoft tyre from Pirelli on offer, this was always likely to be a one-stop race; indeed some teams felt that they could do the entire 260km race distance on a single set of soft tyres, if the rules allowed it. This actually led to a gamble by Toro Rosso on Carlos Sainz’ car; the Spaniard was penalised for missing an FIA weight check during qualifying and had to start from the pit lane.

The team pitted him early on lap 12, without losing significant track position and he then benefitted as others ahead of him pitted or dropped out of the race, to gain places up to 10th place, which is an excellent return from such a lowly start position. He had no problem doing 66 laps on a set of tyres.

This durability has led many to question why Mercedes and Lewis Hamilton went for the late pit stop which cost him the win. He didn’t need to do it from a tyre wear or degradation point of view. He had stopped quite late to get off the supersoft tyres, Lap 38, and therefore he would have no problem at all to reach the finish on the soft tyres he was using.

Hamilton admitted that he was trying to read the race from the cockpit and took visual cues from the screens around the track, which showed the Mercedes mechanics in the pit lane, which is standard practice for Safety Car situations. He felt that his tyres would be a problem after the restart and did not want to be vulnerable, if the cars behind him made a switch. Initially when he made the request to stop, the team told him to stay out, but then they changed the decision at the last moment, to bring him in.

The problem was that in the decisive moment before making that call, they had lost an accurate track of the gaps to the cars behind. Although Toto Wolff said that this was a unique situation as GPS positioning doesn’t work in Monaco, in fact there is a back-up system called “Dead Reckoning”, which uses timing loops at every marshals post; there are 19 of them around the 3.37km Monaco track. So they have a pretty accurate idea of where the cars are and the gaps are constantly updated.

Where it all went wrong was when he caught the Safety Car in the section between Mirabeau Corner to Tabac, during which Hamilton lost nine seconds to Rosberg. He had a lead of 26.802 seconds at Casino Square and it bled away to 18.062s by Tabac Corner. He lost a further two seconds in the swimming pool section between Tabac and the pit entry. So doing the maths was a sliding scale against something you cannot control, which is the pace of the Safety Car versus the pace of Rosberg and Vettel some way behind.

The Safety Car with Hamilton behind it was travelling more slowly than the stipulated target lap time the cars must drive at during a Safety Car period, hence Rosberg and Vettel closing the gap. So whereas he had enjoyed a 26 second lead over Rosberg after the Casino Square on Lap 65, by the time he entered the pit lane, it was more like 15 seconds.

To make a stop at racing speeds in Monaco you need a gap of 22 seconds, that reduces to under 15 seconds under a Safety Car, as the cars on track are travelling more slowly. As Hamilton approached Rascasse and the point of no return on coming into the pits, he lost another two or three crucial seconds – the team should have seen from the „Dead Reckoning“ system that the gap was too marginal to stop safely, yet in a split second yes or no decision, they went the wrong way; he was allowed to pit and this was where the error occurred.

To make a stop at racing speeds in Monaco you need a gap of 22 seconds, that reduces to under 15 seconds under a Safety Car, as the cars on track are travelling more slowly. As Hamilton approached Rascasse and the point of no return on coming into the pits, he lost another two or three crucial seconds – the team should have seen from the „Dead Reckoning“ system that the gap was too marginal to stop safely, yet in a split second yes or no decision, they went the wrong way; he was allowed to pit and this was where the error occurred.

Hamilton didn’t just want to win Monaco, he wanted to dominate it and he said after the race of his pace relative to Rosberg, “I blew him away.” This had been his objective for the weekend and it is likely it was behind his concern over the tyres for the restart.

On fresh supersofts after the restart he would have pulled away and won by probably 30 seconds. His part in motivating the decision to stop on Lap 65 should not be underestimated, but the strategy team has to make the final call and they lost track of the real gap and the fact that the Safety Car with Hamilton behind it was travelling more slowly than the target lap times the cars must drive at during a Safety Car period.

Fear of Ferrari

Another motivator the team owned up to for the controversial Hamilton second stop was Mercedes’ fear of Ferrari, which seems surprising given how much of a margin Hamilton had over his pursuers in Monaco. They were concerned that if Vettel stopped for new supersofts during the Safety Car period, that at the restart he would be able to attack both Mercedes on new tyres while they were struggling with grip on used softs that had lost temperature and pressure at low speeds behind the Safety Car. It seemed a remote probability. Ricciardo pitted on the same lap as Hamilton for supersofts and went on to pass Raikkonen, so it was possible.

Verstappen had done something similar on Lap 48, switching to supersofts and had passed team mate Sainz and the Williams of Valtteri Bottas; he was trying to pass Grosjean when the accident happened. But as it showed when Hamilton on new supersofts could not pass Vettel after the restart, the very thing Mercedes feared would have been unlikely to come to pass.

At the previous race in Spain, Mercedes was dominant and the team had no concerns about being attacked by Sebastian Vettel at any stage. However since losing the race to them in Malaysia, they have shown some concern at times about what Ferrari might do and this was another example, one that other teams’ strategists have been somewhat surprised by, given that Hamilton had a 25 second lead at the start of the ill-fated Lap 65.

At the previous race in Spain, Mercedes was dominant and the team had no concerns about being attacked by Sebastian Vettel at any stage. However since losing the race to them in Malaysia, they have shown some concern at times about what Ferrari might do and this was another example, one that other teams’ strategists have been somewhat surprised by, given that Hamilton had a 25 second lead at the start of the ill-fated Lap 65.

In the confusion after Verstappen and Grosjean’s accident, he had added six seconds to his lead, which had been 19.196 secs on the previous lap. But, as we have seen, that advantage slipped away quickly.

Verstappen and Sainz shine in different ways

The turning point of the race was the Verstappen accident, caused by the high speed differential with Roman Grosjean’s Lotus as the Dutchman tried to come through on new supersoft tyres. It is interesting to look at the different ways Toro Rosso approached strategy for its two drivers.

Verstappen had pitted onto new supersofts on Lap 46 in order to attack. The reason for this was that he had lost half a minute with a slow pit stop and was trying to make up for lost time. Early on in the race, the midfield had been split by Pastor Maldonado’s brake problem, but Verstappen had shown the pace to bridge the gap back up to Sergio Perez. After he lost time and track positions, he was on the attack and stopping him a second time for supersofts was Toro Rosso’s way of trying to get him back into the points.

He came through his team-mate and Bottas easily enough, his target being to get back to where he had been with Button and Nasr. It was the right idea and he was caught out by Grosjean’s position on the circuit and braking for the corner. It was unfortunate, as he had enjoyed a strong weekend. The contrast with his team mate Carlos Sainz is interesting, Sainz gets the results through applying calmness to his undoubted speed, whereas the less experienced Verstappen doesn’t always take advantage of his performance and pace.